Overview

- Hospitals and clinics worldwide are categorized into tiers based on their service capabilities, infrastructure, and specialization.

- These tiers help governments, healthcare providers, and patients understand the level of care available at a facility.

- Tier systems vary by country, influenced by healthcare policies, economic conditions, and medical needs.

- Primary, secondary, and tertiary care levels are common classifications, though some nations use additional categories.

- Understanding these tiers aids in efficient resource allocation and patient referrals across healthcare systems.

- This article examines global hospital and clinic tier systems, their structures, and their implications for care delivery.

Details

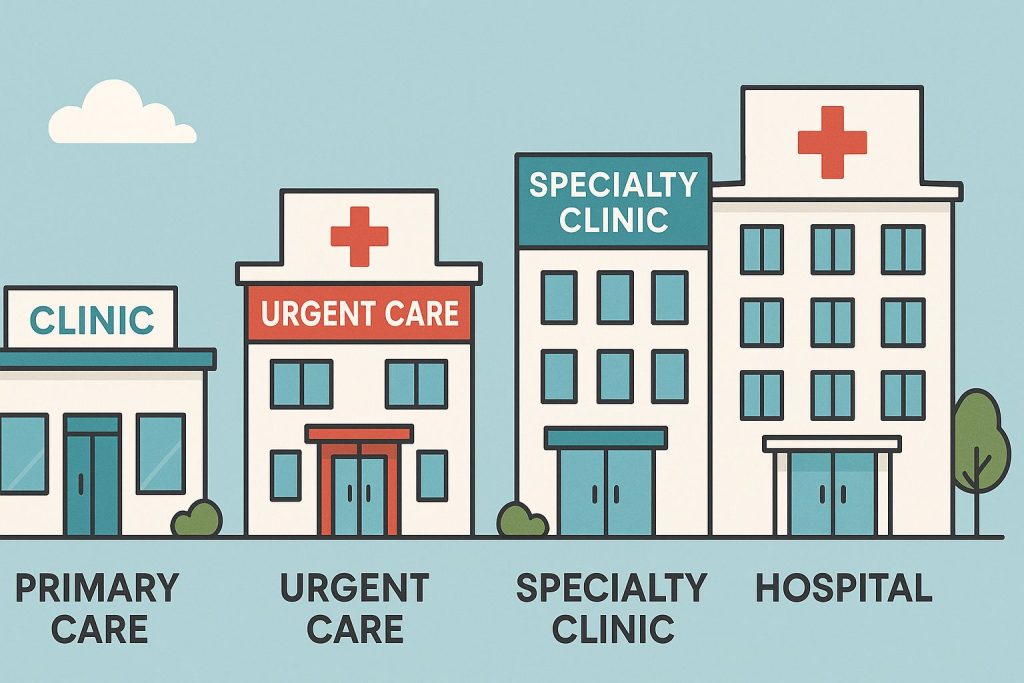

Defining Hospital and Clinic Tiers

Hospitals and clinics are organized into tiers to reflect their capacity to provide medical care, ranging from basic to highly specialized services. These tiers are typically defined by the complexity of treatments offered, the availability of advanced equipment, and the expertise of medical staff. In most countries, the tier system aligns with the concepts of primary, secondary, and tertiary care, though specific definitions and additional levels vary. For instance, primary care facilities focus on general health services, while tertiary care centers handle complex conditions requiring advanced technology. The tier system ensures that patients receive appropriate care based on the severity of their conditions. Governments and health organizations use these classifications to streamline healthcare delivery and optimize resource use. In developing nations, tier distinctions may also reflect infrastructure limitations, such as access to electricity or clean water. In contrast, wealthier countries often emphasize specialization and cutting-edge technology in their tier definitions. The World Health Organization (WHO) provides guidelines for categorizing facilities, but local adaptations are common. Understanding these tiers is essential for navigating global healthcare systems effectively.

Primary Care Facilities

Primary care facilities form the foundation of most healthcare systems, offering basic medical services to communities. These include general clinics, outpatient centers, and small hospitals that address common illnesses, preventive care, and minor injuries. Typically, primary care providers include general practitioners, nurses, and community health workers. They focus on routine check-ups, vaccinations, maternal care, and treatment of conditions like infections or hypertension. These facilities are often the first point of contact for patients, making them critical for early diagnosis and health education. In rural or underserved areas, primary care centers may be the only accessible healthcare option. They usually lack advanced diagnostic tools or surgical capabilities, referring complex cases to higher-tier facilities. In many countries, primary care is subsidized or free to ensure universal access. For example, India’s primary health centers serve millions in rural areas, while the UK’s general practitioner clinics anchor its National Health Service. Despite their importance, primary care facilities often face challenges like understaffing or limited funding.

Secondary Care Facilities

Secondary care facilities provide more advanced services than primary care, often including specialized consultations and short-term hospitalizations. These hospitals and clinics employ specialists like cardiologists, orthopedists, or pediatricians to treat conditions requiring targeted expertise. Secondary care includes diagnostic procedures like X-rays, ultrasounds, or minor surgeries that primary care centers cannot perform. Patients are typically referred to secondary facilities by primary care providers when their conditions exceed basic treatment capabilities. These facilities bridge the gap between general care and highly complex interventions, serving as a critical intermediary in the tier system. In many countries, secondary care hospitals are located in urban or semi-urban areas, making access a challenge for rural populations. They often have emergency departments, maternity wards, and basic intensive care units. For instance, district hospitals in Kenya or community hospitals in the United States exemplify secondary care. Funding and staffing shortages can limit their effectiveness, particularly in low-income regions. Secondary care is vital for reducing the burden on tertiary facilities by managing moderately complex cases.

Tertiary Care Facilities

Tertiary care facilities represent the highest tier of healthcare, offering specialized and complex treatments for severe conditions. These include large teaching hospitals, research centers, and specialized institutions equipped with advanced technology like MRI scanners or robotic surgery systems. Tertiary care involves highly trained specialists, such as neurosurgeons, oncologists, or transplant surgeons, who manage rare or life-threatening conditions. Patients are referred to these facilities when secondary care cannot address their needs, often for procedures like organ transplants or cancer therapies. Tertiary hospitals also conduct medical research and train healthcare professionals, contributing to advancements in medicine. They are typically located in major cities, which can create access disparities for rural patients. In countries like Germany or Japan, tertiary care centers are renowned for their cutting-edge treatments and high success rates. However, their services are costly, and wait times can be long in publicly funded systems. In developing nations, tertiary care is often limited to a few flagship hospitals. These facilities are essential for tackling the most challenging medical cases but require significant investment to maintain.

Variations Across Countries

The structure and naming of hospital tiers vary significantly across countries, reflecting differences in healthcare systems and economic resources. In the United States, hospitals are often classified by service level, such as community hospitals (secondary) or academic medical centers (tertiary). In contrast, India uses a more formalized system of primary health centers, community health centers, and district hospitals. Some countries, like China, incorporate additional tiers, such as township hospitals or provincial hospitals, to address regional needs. These variations are influenced by factors like population density, disease prevalence, and government policies. For example, in densely populated urban areas, secondary and tertiary facilities are more common, while rural regions rely heavily on primary care. In low-income countries, the tier system may be less defined due to resource constraints, with many facilities functioning at a primary level. High-income nations, like Canada or Australia, often have well-funded tier systems with clear referral pathways. International organizations like the WHO encourage standardized classifications, but local adaptations persist. These differences highlight the importance of context in understanding global healthcare tiers.

Challenges in Tiered Systems

Tiered healthcare systems face numerous challenges that impact their effectiveness in delivering care. One major issue is the uneven distribution of resources, with tertiary facilities often concentrated in urban areas, leaving rural populations underserved. Primary care facilities, while more widespread, frequently lack adequate staff, equipment, or medications. In many developing countries, secondary care hospitals struggle to bridge the gap between primary and tertiary levels due to limited funding. Referral systems can also be inefficient, causing delays in treatment or miscommunication between facilities. For example, in sub-Saharan Africa, patients may travel long distances to reach secondary or tertiary care, increasing costs and risks. In wealthier nations, challenges include long wait times for specialized care and high costs at tertiary levels. Workforce shortages, particularly of specialists, affect all tiers in many regions. Additionally, disparities in healthcare access based on income or insurance coverage exacerbate inequities within tiered systems. Addressing these challenges requires coordinated policy efforts and increased investment in infrastructure and training.

Role of Technology in Tiered Healthcare

Technology plays a critical role in enhancing the capabilities of hospitals and clinics across all tiers. At the primary care level, telemedicine and mobile health applications improve access to consultations and health education, especially in remote areas. Secondary care facilities benefit from diagnostic tools like CT scanners or laboratory equipment, enabling more accurate diagnoses. Tertiary care centers rely heavily on advanced technologies, such as robotic surgery systems or proton therapy for cancer treatment. Electronic health records (EHRs) facilitate coordination between tiers by ensuring patient data is shared efficiently. In countries like South Korea, technology-driven healthcare systems have improved outcomes across all tiers. However, technology adoption is uneven, with low-income countries often lacking access to basic diagnostic tools. High costs and maintenance requirements can also limit the scalability of advanced equipment in developing regions. Training healthcare workers to use new technologies is another hurdle, particularly in understaffed facilities. Despite these challenges, technology continues to transform tiered healthcare by improving efficiency and patient outcomes.

Financing and Accessibility

The financing of tiered healthcare systems significantly affects their accessibility and quality. In publicly funded systems, like those in the UK or Canada, primary care is often free or low-cost, while tertiary care may involve wait times. In contrast, private healthcare systems, common in the United States, can make tertiary care accessible to those with insurance but costly for others. In low-income countries, out-of-pocket payments for secondary or tertiary care create financial barriers for many patients. Government subsidies and international aid often support primary care but are insufficient for higher tiers. For example, in Nigeria, public hospitals at all tiers are underfunded, leading to reliance on private clinics. Universal health coverage initiatives aim to improve access across tiers, but implementation varies widely. In wealthier nations, insurance models help distribute costs, though disparities persist for uninsured populations. Accessibility also depends on geographic factors, with rural areas often lacking secondary or tertiary facilities. Effective financing strategies are crucial for ensuring equitable access to all tiers of care.

Impact on Patient Outcomes

The tiered structure of healthcare systems directly influences patient outcomes by determining the level of care available. Primary care facilities excel at preventive measures and early interventions, reducing the incidence of severe conditions. Secondary care ensures timely treatment of moderately complex cases, preventing complications that require tertiary intervention. Tertiary care facilities achieve high success rates for critical conditions, such as heart surgeries or cancer treatments. However, inefficiencies in referral systems or resource shortages can lead to delays, worsening outcomes. For instance, in rural India, limited access to secondary care can result in untreated conditions progressing to critical stages. In contrast, well-coordinated systems, like those in Sweden, achieve better outcomes through seamless tier transitions. Patient education also plays a role, as awareness of when to seek higher-tier care can prevent delays. Socioeconomic factors, such as poverty or lack of transportation, further impact outcomes across tiers. Overall, the effectiveness of tiered systems in improving health depends on their integration and accessibility.

Future Trends in Tiered Healthcare

The future of tiered healthcare systems is shaped by evolving medical needs, technological advancements, and policy reforms. Aging populations in countries like Japan and Germany are increasing demand for tertiary care, straining resources. At the same time, global health initiatives are prioritizing stronger primary care to address chronic diseases and pandemics. Telemedicine and artificial intelligence are expected to enhance all tiers by improving diagnostics and patient monitoring. For example, AI-driven tools can assist primary care providers in detecting early signs of cancer, reducing referrals to higher tiers. In developing nations, mobile clinics and community health workers are expanding primary care access. Policy efforts are also focusing on reducing disparities between urban and rural healthcare facilities. International collaborations, such as those led by the WHO, aim to standardize tier definitions and improve global health equity. However, funding remains a critical challenge, particularly for low-income countries. The future of tiered systems will depend on balancing innovation with equitable access to care.

Case Study: Tiered Systems in Brazil

Brazil’s Unified Health System (SUS) provides a practical example of a tiered healthcare system in a middle-income country. Primary care is delivered through Family Health Strategy units, which focus on preventive care and community outreach. Secondary care is provided by municipal hospitals and specialized clinics, offering diagnostic and surgical services. Tertiary care is concentrated in university hospitals and regional centers, handling complex cases like organ transplants. The SUS aims to provide universal access, but regional disparities persist, with rural areas often limited to primary care. Funding challenges and long wait times for tertiary care are common issues. Technology, such as telemedicine, is being integrated to improve access in remote regions. Brazil’s system demonstrates the strengths of tiered care in ensuring broad coverage but also highlights challenges like resource allocation and infrastructure gaps. Lessons from Brazil can inform other countries seeking to balance cost, access, and quality. The SUS continues to evolve through policy reforms and international partnerships.

Case Study: Tiered Systems in Germany

Germany’s healthcare system is a model of efficiency in tiered care, supported by a mix of public and private funding. Primary care is provided by general practitioners and small clinics, emphasizing preventive care and chronic disease management. Secondary care includes regional hospitals with specialized departments for cardiology, orthopedics, and other fields. Tertiary care is delivered by university hospitals and specialized centers, renowned for advanced treatments like robotic surgeries. The system ensures universal coverage through mandatory health insurance, reducing financial barriers. Referrals between tiers are well-coordinated, minimizing delays in treatment. Germany’s investment in technology, such as EHRs and telemedicine, enhances efficiency across all tiers. However, challenges include workforce shortages and rising costs due to an aging population. Rural areas also face access issues, though less severe than in developing nations. Germany’s tiered system illustrates the benefits of strong financing and coordination in achieving high-quality care.

Policy Implications

The structure of tiered healthcare systems has significant implications for health policy and planning. Governments must balance investment across tiers to ensure equitable access and efficient resource use. Strengthening primary care can reduce the burden on higher tiers by preventing disease progression. Policies that improve referral systems, such as standardized protocols, can enhance care coordination. Workforce training programs are essential to address shortages, particularly in secondary and tertiary facilities. In low-income countries, international aid can support infrastructure development at all tiers. Wealthier nations must address cost containment while maintaining quality, especially in tertiary care. Policies promoting technology adoption, like telemedicine subsidies, can bridge access gaps. Public-private partnerships can also enhance resource availability, as seen in countries like Singapore. Effective policies are critical for optimizing tiered systems to meet diverse population needs.

Global Health Equity

Tiered healthcare systems play a central role in addressing global health equity, but disparities remain a challenge. In low-income countries, primary care is often the only accessible tier, limiting treatment options for complex conditions. Wealthier nations provide broader access to all tiers but still face inequities based on income or geography. International organizations advocate for universal health coverage to ensure all tiers are accessible regardless of socioeconomic status. Initiatives like the WHO’s primary healthcare framework aim to strengthen lower tiers globally. Technology transfers, such as affordable diagnostic tools, can enhance care in resource-poor settings. Training programs for healthcare workers are also critical to building capacity across tiers. Addressing equity requires coordinated efforts between governments, NGOs, and private sectors. Success stories, like Rwanda’s community-based health model, show the potential for equitable tiered systems. Closing the gap in access to all tiers remains a global health priority.

Integration of Traditional Medicine

In some countries, tiered healthcare systems integrate traditional or alternative medicine, particularly at the primary care level. For example, in China, traditional Chinese medicine (TCM) is offered alongside Western medicine in clinics and hospitals. Primary care facilities may provide acupuncture or herbal treatments for common ailments. Secondary and tertiary facilities often combine TCM with advanced diagnostics or surgeries for holistic care. In India, Ayurveda and homeopathy are recognized within the healthcare system, with dedicated clinics at the primary level. Integrating traditional medicine can improve access and cultural acceptance of healthcare services. However, challenges include ensuring evidence-based practices and standardizing training for practitioners. In Africa, traditional healers are sometimes incorporated into primary care to address community needs. These integrations highlight the flexibility of tiered systems in adapting to local contexts. Balancing traditional and modern medicine requires careful regulation to maintain quality and safety.

Emergency Care in Tiered Systems

Emergency care is a critical component of tiered healthcare systems, with each tier playing a distinct role. Primary care facilities provide initial stabilization for minor emergencies, such as cuts or fevers. Secondary care hospitals have emergency departments capable of handling acute conditions like fractures or heart attacks. Tertiary care centers are equipped for life-threatening emergencies, such as severe trauma or stroke, often with specialized units like trauma centers. Efficient triage and referral systems are essential to ensure patients reach the appropriate tier quickly. In many countries, ambulance services facilitate transfers between tiers, though availability varies. For example, in the United States, advanced paramedic services support rapid transport to tertiary centers. In contrast, rural areas in developing nations may lack emergency transport, delaying care. Training emergency personnel and equipping facilities are ongoing challenges. Strengthening emergency care across tiers is vital for improving survival rates and patient outcomes.

Mental Health in Tiered Systems

Mental health services are increasingly integrated into tiered healthcare systems, though coverage varies widely. Primary care facilities offer basic mental health support, such as counseling or medication for common disorders like depression. Secondary care includes psychiatric clinics or hospital wards for conditions requiring specialized care, such as bipolar disorder. Tertiary care provides advanced treatments, like inpatient care for severe schizophrenia or electroconvulsive therapy. Stigma and resource shortages often limit mental health services, particularly in low-income countries. For example, in sub-Saharan Africa, primary care providers may lack training to address mental health issues. In contrast, countries like Australia have robust mental health programs across all tiers. Technology, such as telepsychiatry, is expanding access to care in underserved areas. Integrating mental health into tiered systems requires increased funding and workforce development. Addressing mental health equitably across tiers is a growing priority in global healthcare.

Training and Workforce Development

The effectiveness of tiered healthcare systems depends heavily on a skilled workforce, requiring ongoing training and development. Primary care providers need training in general medicine and preventive care to serve diverse populations. Secondary care specialists require advanced education in fields like surgery or radiology. Tertiary care demands highly specialized training for complex procedures, often provided through medical schools or fellowships. In many countries, workforce shortages are a significant barrier, particularly in rural areas. For example, in India, primary care centers often lack doctors, relying on nurses or community health workers. In wealthier nations, aging workforces and burnout pose challenges across all tiers. International programs, such as those by Médecins Sans Frontières, help train providers in low-resource settings. Technology, like online training platforms, is also expanding access to education. Investing in workforce development is essential for sustaining tiered systems and improving care quality.

Environmental and Social Determinants

Environmental and social factors significantly influence the performance of tiered healthcare systems. Access to clean water, sanitation, and nutrition affects the demand for primary care services. Poverty and education levels impact patients’ ability to seek timely care, often leading to reliance on higher tiers for advanced conditions. Urbanization concentrates secondary and tertiary facilities in cities, leaving rural areas underserved. Climate change is also increasing health challenges, such as infectious diseases, that strain all tiers. For example, in Bangladesh, flooding exacerbates the need for primary care in affected areas. Social determinants, like gender or ethnicity, can create barriers to accessing any tier. Health policies must address these factors to ensure equitable care delivery. Community-based interventions, such as mobile clinics, can mitigate some challenges. Understanding these determinants is critical for designing resilient tiered systems.

Conclusion

Hospital and clinic tiers provide a structured approach to delivering healthcare, from basic services to complex treatments. Primary care ensures broad access, secondary care addresses specialized needs, and tertiary care tackles the most severe conditions. Variations in tier systems reflect local contexts, with challenges like resource disparities and access inequities persisting globally. Technology, financing, and workforce development are key to strengthening these systems. Case studies from Brazil and Germany highlight both successes and areas for improvement. Future trends, such as telemedicine and AI, promise to enhance all tiers, but equitable access remains a priority. Mental health, emergency care, and traditional medicine are increasingly integrated, reflecting diverse health needs. Policy reforms and international collaboration are essential for optimizing tiered systems. Environmental and social factors further shape their effectiveness, requiring holistic approaches. Understanding global hospital and clinic tiers is crucial for improving health outcomes worldwide.